Freemasonry uses many symbols and emblems to represent its beliefs, philosophies, and principles. These symbols come from a wide range of sources but have been incorporated into Masonic traditions over the centuries. Some symbols represent moral virtues, others refer to architectural and geometric principles, while some relate to tools of the stonemason’s trade. In this article, we will explore some of the most common Masonic symbols and emblems, their origins, and meanings. Understanding these symbols provides insight into the values, teachings, and rituals of Freemasonry.

The Square and Compasses

The most widely recognized Masonic symbol is the square and compasses. This emblem depicts a square, an important tool in stonemasonry, along with a compass sitting atop the square. The square represents morality, truthfulness, and honesty. The compass indicates self-restraint, discipline, and a way to stay within boundaries. Together, the square and compass embody the efforts of Freemasons to integrate morality into their lives and actions. This combined emblem appears on Masonic buildings, documents, and regalia as a reminder to Masons to live their lives and conduct their affairs upon the square.

The Letter “G”

The letter “G” stands at the center of the square and compasses. This letter has several meanings in Freemasonry. First, it stands for Geometry, an influential science through which many Masonic symbols and teachings are presented. It also means God, referring to the Supreme Being of each individual Mason’s faith. Finally, some believe it represents the name Hiram Abiff, the master builder of Solomon’s Temple and central figure of Masonic ritual. The precise meaning can vary between Masonic jurisdictions but always relates to central Masonic principles.

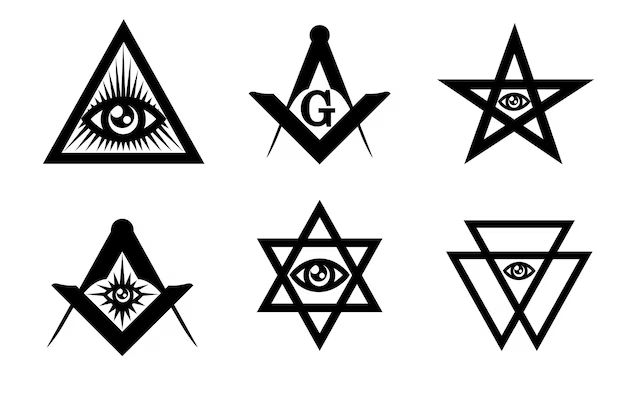

All-Seeing Eye

The all-seeing eye is a triangle or pyramid with an eye inside, sometimes surrounded by rays of light. This image represents God keeping watch over humanity and his omniscience. The eye inside a triangle specifically relates to the Christian Trinity. Masons use the all-seeing eye as a reminder that their thoughts and deeds are always observed by a Supreme Being. It encourages living an ethical, moral life.

The Volume of Sacred Law

When a Masonic lodge is in session, the Volume of Sacred Law sits open upon the altar at the center of the lodge room. This book is the holy text for that lodge’s particular faith; it may be the Bible, Torah, Quran, or other text depending on the Masons present. Having their Volume of Sacred Law present reminds Masons of their dependence on God and his divine wisdom. It binds them to their faith and its morals.

The Blazing Star

The blazing star, or glory, is a five-pointed star that relates to the five points of fellowship which unite Masons. The star’s light refers to enlightenment, education, divine providence, and the life-giving properties of the sun. It reminds Masons to spread light and impart knowledge and wisdom wherever they go. The blazing star is also seen as representing Sirius, the dog star, which holds an important place in Masonic teachings.

The Beehive

In Masonic symbolism, the beehive represents industry, cooperation, and working together for the greater good. A beehive depends on thousands of worker bees laboring together, coordinating their efforts and putting the needs of the hive above personal gain. Masons use the image of the beehive to illustrate ideals of teamwork, community, and mutual support which they strive to put into practice.

The Acacia

The acacia is a thorny bush native to the Middle East. In Masonic ritual, it has several symbolic meanings. Its thorns represent sin, suffering, and errors, while its flowers and leaves signify purity, innocence, and healing. The acacia’s sap refers to immortality. As acacia wood was used to build the tabernacle, it represents sacredness and consecration to God. The most famous Masonic meaning of acacia relates to the legend of Hiram Abiff’s grave; a sprig of acacia marked the spot where he had been buried.

The Sprig of Acacia

As part of the story of Hiram Abiff, the sprig of acacia plays a special role. When Hiram is assassinated and buried, the acacia springs up where he is laid to rest. It is used as a symbol for his soul surviving in eternal life. In this way, the sprig of acacia became synonymous with immortality, rebirth, and the resurrection of the spirit. It represents Masons’ faith in an afterlife in the celestial lodge above.

The Broken Column

The broken column shows a Doric column snapped off midway, sometimes with a piece laying near the base. This represents the untimely death of Hiram Abiff. More broadly, it symbolizes the unfinished nature of human life that gets cut off by mortality. The broken column reminds Masons of the brevity and fragility of life and the importance of accomplishing one’s work while there is still time.

The Sword Pointing to a Naked Heart

This imagery shows a human heart being pierced or threatened by a sword. The heart symbolizes an individual’s conscience and morality, while the sword indicates the consequences of straying from those values. This emblem reminds Masons to hold true to their inner sense of virtue, morality, and ethics despite outside pressure or temptation. It serves as a warning not to let external forces turn them from their duty.

The Anchor and the Ark

In Masonic symbolism, the anchor and the ark represent hope, safety, unity, perseverance, and strength. The anchor is seen as stabilizing the Mason to keep him firmly tethered to his principles and beliefs. The ark equates to the church, faith, or Masonic ideals that empower him to weather life’s storms. Together, the anchor and ark urge Masons to remain grounded in their faith and conviction despite difficult circumstances.

The Hourglass

For Masons, the hourglass signifies the passage of time and the shortness of human life. The sands running out reminds them to number their days and use their time well. The hourglass urges acting with diligence, seizing opportunities, finishing work, and preparing spiritually as mortality runs its steady course. Masons see time as a gift from God not to be wasted but used prudently and for the benefit of humanity.

The Scythe

The scythe appears frequently in Masonic art and on headstones with Masonic markings. The scythe represents the great harvester, death itself, which cuts human life short at its destined time. The scythe symbolizes that death comes without distinguishing between roles and stations; the scythe levels all equally. For Masons, it signifies the importance of living well and coming to one’s end with faith and virtue.

The Three Pillars

Three pillars often appear in Masonic symbolism representing three main principles of the fraternity: Wisdom, Strength, and Beauty. Wisdom relates to education, pursuing knowledge, and strengthening the mind. Strength indicates fortitude in defending one’s ideals and convictions. Beauty implies adherence to high moral standards and maintaining an inner spirit of kindness. The three pillars urge Masons to develop themselves fully in mental, physical, and spiritual ways.

The Three Step Symbol

The three steps or stairs depict the stages of human life. The first step signifies youth and coming into light or knowledge. The second step relates to manhood and developing maturity. The third step represents old age leading to death and immortality. For Masons, the three steps remind them of human progress from ignorance to enlightenment, from this world to the eternal life beyond.

The Trestleboard

The trestleboard is a design board used by architects and builders to outline their plans. In Freemasonry, it represents the moral blueprint toward which Masons should build their lives. The designs on the trestleboard signify Masonic lessons and standards for character which members strive to inscribe on their hearts and follow in their lives. It refers to the fraternity’s search for spiritual knowledge and moral perfection.

The Skull and Crossbones

While a grim symbol, the skull and crossbones carry important meaning in Masonic teachings. The skull represents mortality and the crossbones imply resurrection. Together, they remind Masons of the brevity of life and necessity of preparation for death. The skull and crossbones signify that death comes to all, but the soul crosses over to everlasting life for those who have lived well and faithfully.

The Coffin

Coffins are occasionally seen in Masonic rituals and symbolism. Like the skull and crossbones, the coffin reminds participants of human mortality and the importance of living ethically and honestly. Masonic coffin symbolism stresses the need for mental, spiritual, and moral preparation for the time when one will inevitably die. By keeping death in mind, Masons use their limited time wisely.

The Crossed Swords

Two crossed swords pointed downward symbolize justice and resolution of conflict. The swords bar confrontation from moving forward, favoring peaceful mediation instead. In some Masonic rites, crossed swords sit on top of a Holy Book, relating justice to divine law and morality. For Masons, the crossed swords represent the restraint of destructive passions and the triumph of harmony and compassion.

The All-Seeing Third Eye

A single eye depicted inside a triangle, surrounded by rays of light is known as the all-seeing third eye. In addition to the triangle representing the Trinity, the third eye symbolizes enlightenment and opening one’s mind to divine wisdom and truths. The eye represents guidance from above that transcends ordinary sight. For Masons, an open third eye signifies insight, clarity of thought, and knowledge gained from the Supreme Being.

The Seven Liberal Arts and Sciences

Masonic teachings often refer to the importance of the seven liberal arts and sciences: grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, music, and astronomy. In Masonic symbolism, gaining knowledge of these disciplines represents well-rounding oneself through education and mental cultivation. This emphasis on learning signifies the Masonic desire to improve oneself by developing reason, logic, knowledge, and truthfulness.

The Forty-Seventh Problem of Euclid

Euclid’s forty-seventh problem involves the Pythagorean theorem for building right triangles. Masonic symbolism draws on geometry heavily, including frequent references to the forty-seventh problem. For Masons, Euclid’s theorem represents moral rectitude, fairness, balance, lawfulness, and high standards. Masonic drawings of the forty-seventh problem emphasize the fraternity’s respect for order, ethics, and procedural regularity.

The Masonic Ring

Masons often wear rings bearing Masonic symbols, given upon initiation into the brotherhood. The Masonic ring reminds wearers of their vows, commitments, and obligations to the fraternity. Different symbols on the ring mean different things; the square and compass signify duty to God and fellows, the letter “G” represents the Grand Architect and Geometry, while the skull stands for mortality. Masonic rings bind the wearer to his brothers, ideals, and the timeless truths his symbols express.

Subsidiary Symbols

In addition to major emblems, Masonic symbolism incorporates many minor symbols representing key teachings and principles. These include the beehive (cooperation), plumb (uprightness), level (equality), trowel (service), hourglass (brevity of time), scythe (death as the great leveler), columns (support), and numbers three, five, seven, twelve, and forty-seven, each with specific meanings.

Conclusion

Masonic symbols provide visual representations of the fraternity’s tenets, values, and lessons. These emblems speak to qualities like honor, ethics, morality, restraint, fortitude, and imperfection balanced by eternal hope. For Freemasons, they represent the ideals the brotherhood seeks to impart and make manifest through rituals, education, and living out Masonic principles in daily life. Though centuries old, these symbols still guide Masons today to build their lives—and collectively the moral edifice of humanity—upon the foundation of inner nobility.